- Home

- Helmut Ortner

The Lone Assassin Page 11

The Lone Assassin Read online

Page 11

Nor could the National Socialists complain about a lack of popularity in the provinces. To be sure, it had not been necessary, as it had been in the cities after the Nazis came to power, to declare a temporary cap on new members due to the huge rush; effective May 1, 1933, the party’s regional leadership had been instructed to accept new party members only into the Hitler Youth, the SA, and the SS. Though the rush in the eastern Swabian Alps had not been quite as intense, members flocked to the new national movement in droves there as well. As early as February 25, 1934, Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess, on the radio from Königsplatz in Munich amid the roar of cannons, had administered an oath to almost a million party members: Adolf Hitler is Germany, and Germany is Adolf Hitler. He who pledges an oath to Hitler pledges an oath to Germany.

Along with their counterparts all over the Reich, party members in Königsbronn listened with awe to the mass pledge. Here, too, the local party branch had begun to co-opt the cultural life and all the clubs and societies into the new national movement. Eugen Rau’s private dance group, the local hiking club, and the leftist political parties, whose share of the vote in this region had always been markedly above the national average before the National Socialists took power—these organizations ceased to exist.

Königsbronn, too, had become a “German village”—a village in exemplary conformity with the deceptive propaganda image of the new regime.

* * *

This change over the past several years had not escaped the notice of Georg Elser and Eugen Rau. When the local party members crowded around the Volksempfänger (people’s radio receiver) in the Hecht tavern to listen raptly to the voices of Goebbels and Hitler and to propose toasts to the “national revolution” at the end of the speeches, Georg and Eugen would leave the room. Politics was not their thing—especially not the politics of the National Socialists.

Regarding Elser’s political attitudes, Georg Vollmann, the local branch leader of the party until 1938, later testified that he was neutral, was not a member of any party, and did not get involved in any debates. While I was local branch leader, I once observed Elser turning around and leaving during a parade. That was no big deal, but it struck me that he was no man of the Third Reich.

While the local branches in the provinces were marching in street parades, a first wave of “purges” had already claimed numerous victims throughout the Reich. More than eighty people—including “old fighters,” SA comrades, and troublesome opponents—were murdered on the “Night of the Long Knives,” when the so-called Röhm Putsch was put down at the end of June 1934. This time, no one could speak of a “night of the miracle,” as the propagandists had when Hitler gained power. Instead, the Nazi regime carried out a “night of terror,” committing a series of political murders. Among the victims were former chancellor Kurt von Schleicher; his closest colleague General von Bredow; the former Reichsorganisationsleiter of the Nazi Party Gregor Strasser; and Gustav von Kahr, whom Hitler had urged to join his putsch in Munich in 1923. Father Bernhard Stempfle, editor of the Miesbacher Anzeiger, who was credited in party circles with having helped the Führer compose Mein Kampf, was killed in cold blood, as were the closest colleagues of Vice-Chancellor von Papen.

On July 2, 1934, Hitler expelled the dead Röhm from the SA and the party. At the same time, a man named Heinrich Himmler stepped forward as chief of the SS. When President Paul von Hindenburg died that same year on August 2, Hitler’s last hurdle on the path to absolute power had been removed. Now he appointed himself head of state—one people, one Reich, one Führer.

With the exception of the victims, not many Germans seemed interested in the fact that a year later an unknown ministry official named Hans Globke—who would become quite well known after the world war as Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s state secretary—wrote a commentary on the Nuremberg Laws that ushered in a previously unimaginable degradation and persecution of the Jewish population. It was more important to the German Volk that there were no longer 6 million unemployed, but only 2.5 million. The propaganda organizations of the Nazi regime disseminated their “success reports” into the most remote corners of the Reich, while the party faithful in the regions and villages cheered with their shouts of “Heil,” hung swastika flags in their windows, and marched in step through the village streets—in Königsbronn, too. There were few who did not join in the Greater German jubilation.

Among them was Georg Elser, who not only lacked enthusiasm for the Third Reich, but also had never liked political debates and demonstrations.

My parents have always been completely apolitical. I remember that my father only voted when someone came to get him. I don’t know whom he voted for. When I reached voting age, he definitely never influenced me in any way. I think my mother voted, but she never said anything about whom she voted for, he later testified during his interrogations in Berlin, in response to questioning about his political development.

His mother confirmed those statements: In our family no one was really concerned with politics. My husband wasn’t interested in it. You did your work and didn’t worry about parties and politics. If a political topic did come up, Georg uttered one or two sentences and then let the matter rest.

He had almost nothing to say about politics and was not at all interested in it. If I myself or other people grumbled in his presence about measures taken by the Nazi Party, he was always very consistent in his statements. He always said: You’re either for them or against them, his girlfriend Elsa recalled. Once, before an election in Königsbronn, she had spoken to him about politics. She had asked him whether he was going to vote, and he had said no. She tried to persuade him to vote, because she was afraid that there might be talk in the small village, but that didn’t matter to him. What do I care what other people say, he responded. Nonetheless, he had no objections to her voting. You have to decide that for yourself, he told her.

Where did it come from, his intuitive aversion to the Nazi regime? Where did this categorical rejection come from? He explained the reasons for it during his interrogation in Berlin.

In my view, circumstances after the national revolution worsened in various ways. For example, I noticed that wages got lower and deductions higher. Furthermore, the workers, in my view, have been under certain constraints since the national revolution. For example, the worker can no longer freely change his place of work as he pleases. Because of the Hitler Youth, he is no longer the master of his children. And he can no longer act so freely with respect to religion.

Though Elser rarely took part in political discussions, he was regarded as leaning toward the left. On the one hand, that might have had to do with the fact that anyone who did not agree with the National Socialists was immediately branded a “communist” and declared an enemy of the people. On the other hand, he did feel most comfortable in like-minded circles, where he could presume kindred attitudes without first having long discussions about politics.

Among the Friends of Nature and the hiking club, which he had joined during his stay in Konstanz, he found an unspoken accord with his sense of what was going on around him, with the way he saw his everyday life and his problems. At that time, he also joined the Red Front Fighters League (Rotfrontkämpferbund, RFB), a militant group associated with the Communist Party. Their sign was a balled fist. Did this membership suit him and his behavior in general?

I was only a dues-paying member, for I never wore a uniform or occupied any official post. Only three times during my whole RFB membership did I attend political meetings—of the Communist Party, of course. I joined the RFB after frequent coaxing by a colleague named F., who was working, as I was, in the clock factory in Konstanz, he later stated.

In Konstanz and Königsbronn, his political attitudes were not the result of ideological thinking, but the expression of his observations of his immediate social surroundings—particularly his firsthand impression that National Socialist policies by no means improved the economic situation of the workers (as Nazi propaganda would have had pe

ople believe), but actually worsened them. This deeply aroused his sense of justice.

I was a member of the woodworkers’ union, because this was the organization of workers in my profession and because you were supposed to be a member of this organization….

Personally, I never got involved in politics. After reaching voting age, I always voted for the Communist Party, because I thought it was a worker’s party and would definitely advocate for the workers, but I never became a member of the party, because I thought it was enough to give them my vote….

As to whether I knew that the Communist Party had the intention and the goal of establishing in Germany a Soviet-style dictatorship or a dictatorship of the proletariat, I have to say that it is not impossible that I heard something like that at some point. But I definitely didn’t think anything of it. All I thought was that you had to strengthen the Communists’ mandate by giving them your vote so that the party could do more for the workers. I never heard anything about a violent overthrow.

I was never interested in the program of the Communist Party. So I cannot say how the economic situation would have changed in the event of a Communist victory. All that was discussed at the meetings was that there should be higher wages, better housing, and things like that. The statement of those demands was enough to make me lean toward the Communists.

In the summer of 1937, Elser rode his bike every morning, weather permitting, to work in Heidenheim. On the way, he lost himself in his thoughts. What would his future be like, especially his relationship with Elsa, who had filed for divorce, left the house she shared with her husband, and moved to her parents’ house in Jebenhausen? On the one hand, he felt secure with Elsa; he loved her almost maternal way of caring for him. Hadn’t he always longed for this affection? His rapport with her parents was good, too. They accepted him—more than that, her father had even offered a few days ago to finance courses in interior architecture for him. “You’re an intelligent fellow,” he had said. “You can make something of yourself.” Plus, Elsa’s parents had held out the prospect of an apartment in their own house for the two of them. “We would just give notice to the tenants,” her father said. Georg had declined both offers. He didn’t want others to be kicked out for his sake; nor did he want Elsa’s father to pay for his studies. No, he didn’t want to have his future made for him, he told Elsa.

He understood that Elsa’s parents were motivated by their desire to help their daughter and her two small children get back on their feet after a failed marriage. Georg seemed to them to be the right man for that. With him by her side, they thought, their daughter Elsa could once again find family happiness. Now, as the first Heidenheim houses were emerging from the morning mist, he thought about the fact that he had once promised to marry Elsa. She should get a divorce, he had told her, and then they could get married. But afterward, he had been overcome by doubts. Could he feed a family? Did he even have a chance of earning enough money in the foreseeable future despite his deductions for the alimony payments?

He had spoken to Elsa about that, and she had tried to reassure him. We’ll manage, she had told him. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. But did he want to continue on this path? For all the love he felt for her, was Elsa the woman with whom he wanted to spend the rest of his life? What if their interests, their characters were too different? Their plans? His plans? What was going to happen with his work? He did not want to work as an unskilled laborer in the long run; though it paid well, it had nothing to do with the craft he had learned and was not what he envisioned doing. How would he escape the cramped circumstances in his parents’ house, where they had now even demanded rent from him for an attic room—a demand he had refused on the grounds that he had worked for years without pay in his parents’ business? How long would he continue to endure his mother’s disapproving glances when Elsa visited him in his room?

Georg was anything but happy that morning. His life seemed to be at an impasse; his own life felt foreign to him. Was there a new prospect in sight? The whole year of 1937 and a large part of 1938 passed without events or changes, he said later in his interrogations. Everything repeated itself: work, the end of the workday, the weekends, the weekly rehearsals with the zither club. Georg experienced a sense of stagnation. His everyday life had become a rigid ritual.

* * *

More so than in previous years, Georg lived the life of a loner. He maintained contact only with Elsa and Eugen. The two of them were the only people whose closeness he not only accepted, but also sought. In taverns, where he often took his meals, he remained a perpetual outsider. There he sat, withdrawn and alone—observing, listening, ruminating. He did what scarcely anyone else did at that time: he measured the Nazi propaganda against social reality. And he made comparisons. During his interrogations in the Berlin Gestapo building, he testified:

When I was earning fifty reichsmarks per week on average in the clock factory in Konstanz in 1929, the deductions for taxes, health insurance, unemployment benefits, and disability insurance amounted to only about five reichsmarks. Today the deductions are already that high for weekly earnings of twenty-five reichsmarks. The hourly wage of a carpenter was one reichsmark in 1929; today an hourly wage of only sixty-eight pfennigs is paid. I can even remember an hourly wage of 1.05 reichsmarks being paid in 1929.

From conversations with various workers, I know that in other occupations, too, the wages declined and the deductions increased after the national revolution….

I made these observations and conclusions in the years leading up to 1938 as well as in the period that followed. Over that time, I realized that the workers are “angry” at the regime for these reasons. I came to these conclusions in general; individual people who said things in this vein I cannot recall. I made these observations in the places where I worked, in taverns, and on the train. I cannot give the names of any individual people, because I don’t know them.

In all his testimony, he was careful not to cause trouble for any colleagues, acquaintances, or friends. But for all the dissatisfaction and “anger” he detected among his fellow workers, it did not escape his notice that there was a majority who rejoiced—in Königsbronn, too. The national enthusiasm—the noisy, wild excitement that had seized the people deep into the provinces—was unabated. But he was not overcome by it. He viewed the regime as dishonest, cynical, and unjust. Whenever the Führer’s voice blared from the radio in the Hecht tavern, he left the room. The grandiose national spectacle provoked in him an intuitive aversion. Amid the myriad shouts of “Heil,” he felt his doubts mounting to despair.

Was there a way out—private or political? His thoughts overwhelmed him. Deadly thoughts …

CHAPTER TEN

The Decision—The Plan

The train rolled slowly into the Munich station. The clock hand moved to seven in the evening as the steam locomotive came to a stop with a loud screech and hiss. The platform and the vast ticket hall were crowded and hectic. A strikingly large number of people were wearing party uniforms. Georg Elser, dressed in a dark wool coat and holding a small travel bag in his right hand, looked even less conspicuous than usual on that evening of November 8, 1938. His slight figure got lost in the uniformed masses. He hastily crossed the hall and then turned right into an adjoining building. Over its entrance was the sign ACCOMMODATIONS OFFICE. He got into the line of people waiting. After a while, he was able to enter.

In this room were several counters. Some members of the public and the staff of the accommodations office were in party uniform, while others were in civilian clothing. I no longer recall whether I was asked for my name and hometown or whether I was asked if I had been a participant in the march in 1923. I believe that I was asked only in what area I would like to stay.

I did not make a particular request in this regard. I was simply handed a piece of paper with the note “Albanistrasse, house number and landlord”… Whether I had to pay anything for the accommodations, I don’t remember. From the accommodations office I

proceeded directly to Albanistrasse. Because I didn’t know my way around Munich, I took the streetcar there. I asked a streetcar conductor for directions to the apartment. On my arrival, I found out that there were no overnight accommodations available. The people attended to me and put me up one floor below with a family whose name I have since forgotten. As far as I recall, I had to sleep on the sofa. I registered my occupancy with the police. When the people asked me, I gave them my real name, Georg Elser, and my place of residence, Königsbronn. I told these people that I only wanted to see Munich.

But Elser had not come to Munich to visit famous tourist destinations such as the Bavaria statue, the Frauenkirche, and the Hofbräuhaus. He had boarded the train in Königsbronn that morning in the knowledge that the reason for his journey could cost him his life. He had traveled via Ulm to the Bavarian metropolis to make the initial preparations for his plan to eliminate the Nazi leadership. He had decided to kill Hitler—on his own. From the daily paper he had learned about the annual meeting of the “old fighters” at the Munich Bürgerbräu Beer Hall, and now he was in this city to observe the course of the event. At the time, I wanted to determine the prospects for putting my decision into action, he later testified.

Around eight o’clock in the evening, Elser left his accommodations on Albanistrasse to walk to the Bürgerbräu Beer Hall in the Haidhausen district. Following directions from the people he was staying with, he started out along the Isar and then crossed the street to head up Rosenheimer Strasse toward the Bürgerbräu Beer Hall. At the point where Hochstrasse turned off to the right, heavy police units blocked the road. On the sidewalk, an endless line had formed, made up of people who had not been admitted into the long-since packed hall. Now they were waiting to see one prominent party figure or another departing after the rally, perhaps even—if only for a few seconds—the Führer. Many of the people had appeared in party uniform. Elser stood in the middle of the crowd until half past ten, when the roadblock was lifted and the masses gradually dispersed. The noise of enthusiasm that had greeted the party leaders as they left the Bürgerbräu Beer Hall faded.

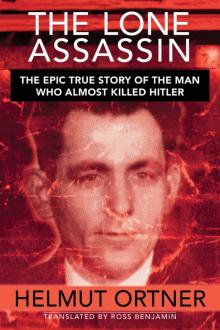

The Lone Assassin

The Lone Assassin