- Home

- Helmut Ortner

The Lone Assassin Page 8

The Lone Assassin Read online

Page 8

He was not paid for his work. For his parents, it went without saying that their oldest son would not demand that. But Georg found it unjust that he also had to do without pocket money. At least a few marks like others his age in the village—was that too much to ask? On Sunday, the only free day of the week, he could not afford a soda with his companions. That embarrassed him, so he preferred just to stay home. On Monday, the torture began anew, and he accepted it without complaints.

When Georg mentioned one evening that he wanted to apply for an apprenticeship as a lathe operator in the ironworks, his father reacted gruffly. “What do you want with that?” he shouted. “I need you. You’re going to take over the business.” But Georg was not impressed by his father’s loud words. He had set his mind on doing an apprenticeship as a lathe operator, just like his friend Eugen. During his interrogations, he described how his decision had ripened.

I got the idea of becoming a lathe operator because my schoolmate Eugen began an apprenticeship in an ironworks immediately after graduation. It was not that he described this job to me in especially glowing terms or brought me pieces he had worked on, but the mere fact that my friend was a lathe operator led me, without my knowing exactly why, to take up this job, too.

My father’s occupation and farm work had never appealed to me. I had worked on the farm less out of pleasure in the work than out of the desire to help my mother. Dealing with horses did not much suit me, and on top of that I had witnessed how various horses had died, which also spoiled my pleasure in transporting lumber.

Despite his father’s reproaches and complaints that he was losing an important worker, Georg stuck to his decision. With his mother’s support, he got the apprenticeship and began training to be a lathe operator in the autumn of 1917. In the factory were two foremen, as many as forty workers, and four other apprentices in addition to Georg. The work was done in two shifts. Later, Georg described his apprenticeship.

In the first three months of my employment in the ironworks, I had to assist the older lathe operators by bringing tools for repair, fetching material, etc. I could not perform any work on my own. At the end of the first three months, I began working on my own at a small lathe under the supervision of the foreman. I had to cut threads, tighten bolts, grind anvils, and perform other, smaller lathe operations. After some time, I began working at a larger lathe, because my model was too light, especially for grinding anvils. In the period that followed, I did somewhat more difficult lathe work.

In the factory, there was often heavy iron dust. In the rear area, iron was heated, and from there warm air permeated the floor. After a few months, Georg noticed that the work did not agree with his health. He complained of headaches and nausea, and often had fevers. Several times he consulted a doctor, who was unable to help him.

At the end of February 1919, he went to the factory office and declared that he wanted to break from his apprenticeship, because he could not tolerate the work. Fourteen days later, he left the ironworks. He was sad to no longer to be able to spend lunch breaks with his friend Eugen and attend the vocational school in nearby Heidenheim, where he had been among the better students in the lathe operating class. On the other hand, it had become clear to him shortly after the beginning of his apprenticeship that he would rather work with wood than iron.

At home, he had amassed a modest tool collection, for which his father had given him money. Otherwise, he had to pay his dues. He was not allowed to keep anything, and he was still not granted an allowance. So what else was there for him to do but spend his Sundays working with wood?

Georg built rabbit hutches, carpentered small bookshelves, and repaired damaged furniture. The decision to give a carpentry apprenticeship a try was thus a natural next step. During his apprenticeship in the ironworks, Georg had made the acquaintance of the master carpenter Sapper, whose workshop was close to his parents’ house. At the behest of his father, he often fetched sawdust and wood chips there, which were used as litter for the barn. There he watched the journeymen at work, which further aroused his interest in carpentry.

On March 15, 1919, Georg began his new apprenticeship. Regarding the work there, he later commented: In the early period of my work I had to make simple boxes, stools, and things like that, which demanded no special skills at all. I had to cut wood to size, plane it, and assemble it. The tasks got progressively harder, and at the end of my apprenticeship I was able to make large and heavy furniture on my own. I took great pleasure and great interest in that work.

Architectural carpentry, which was part of the job, too, appealed less to Georg. He didn’t like the dirt and dust of that coarse work. He preferred the fastidious craftsmanship of cabinetmaking. That was also where he received praise from his master.

Georg was recognized as an extraordinarily talented furniture maker, equally strong in design and construction. Despite his good work, however, the apprentice’s wages were meager. In the first year of the apprenticeship, he received one reichsmark per week; in the second, two; and in the third, four. In the meantime, his parents had stopped withholding the low pay. Georg spent some of the money on clothing, but mainly he purchased carpentry and metalworking tools, such as planes, drills, and files, and set up a small home workshop in his parents’ basement.

Georg was an eager apprentice. He gave no cause for criticism, scrupulously finishing all his tasks and rarely, if ever, missing a day of work. In the spring of 1922, he passed the journeyman’s exam at the Heidenheim vocational school at the top of his class. Everyone was pleased: the master, the journeymen, and even his father. Georg was happy; he had achieved his goal and, for the first time in his life, felt truly appreciated.

Until that December, he remained in his apprenticeship workshop as a journeyman. He then gave notice in order to go work in the Rieger furniture factory in Aalen. The master, who relied on Georg’s outstanding handicraft skills, rejected his resignation. In early 1923, he resubmitted his resignation, which did not meet with the master’s approval that time, either. Then Georg stopped going to work. Fourteen days later, he began his job as a cabinetmaker in Aalen, where his primary occupation was making kitchen and bedroom furniture.

He kept his room in his parents’ house. Every day he took the train early in the morning from Königsbronn to Aalen, and often he did not return until late in the evening. I didn’t make any friendships with my colleagues, he recalled later. In my free time, I did incidental repairs at home. I no longer had time to make things.

Georg’s life consisted mainly of work. Only on Sunday was there time to unwind. That was when he would meet Eugen, his best friend. He trusted him and felt comfortable enough with him to speak his mind. Among other things, he talked to him about quitting his job. “My work isn’t paid properly. You do your work, and the money is worthless. I’d rather quit.”

In the autumn of 1923, he quit. The decision wasn’t easy for him, but unlike many of his colleagues who shared his fate, he accepted the consequences of the rising inflation. They were hard, drastic consequences, which included returning to work on his parents’ farm. Later he recalled that period.

I helped my mother as I had earlier with the work in the fields and assisted my father, who had been carrying on the lumber trade, with logging work, such as trimming, sawing, chopping, and things like that. I did not receive any compensation or allowance from my mother or father. I had room and board at home. In those days, I spent my free time with my friend Eugen, who had a gramophone at home and taught me how to dance. I didn’t do much woodworking at that time. Until the summer of 1924, I worked at home in the way I’ve described.

Around that time, he inquired again about work at a carpenter’s workshop in Heidenheim. Based on his good credentials, he was hired three days later, which was welcome news for him, because the few months at home had shown him that he could no longer work with his father, whose outbursts afflicted him. Despite the fact that he was now twenty-one years old, his father still ordered him around like a yo

ung boy.

In Heidenheim, too, he performed his work to the full satisfaction of his master. The slim journeyman, who built wardrobes and kitchen furniture in the sawdust-covered wood workshop, was known after a short time as an especially capable worker. His colleagues appreciated his quiet, humble manner.

They were thus all the more disappointed when Georg gave notice to the owner in January 1925 because he wanted to move away. The decision to quit his job again had nothing to do with the conditions at his workplace. Though he sometimes worried that he could not sufficiently perfect his technical ability there and did not often feel challenged in his craft, his decision was an expression of more basic considerations.

He had become aware in recent weeks that he found life in Königsbronn constricting, paralyzing, and depressing. He felt demoralized by the irascible, unrestrained behavior of his father, who increasingly suffered from alcoholism; the lamentable situation of his mother, who could not protect herself from her husband’s attacks and for whom he felt sympathy without being able to do anything to help her; and the superficial, distant relationships with his siblings, who did not share his interests any more than he did theirs.

My brother had a somewhat unique character. He was taciturn and did not have much to do with us siblings, but always went his own way. Thus his sister Maria characterized him later. And Leonhard, his younger brother by ten years, recalled, As a child, and later on, too, I didn’t get along especially well with my brother Georg.

Georg had a taciturn and reserved nature. He didn’t talk much and avoided debates, whatever the topic. He made few close friends among his schoolmates and later among his colleagues. A rather quiet, sensitive, musical type, he played the flute and accordion in school and later performed as an entertainer for small groups. He was well liked. He was especially popular with girls, because he was not a loud reveler like the other boys.

Georg was a loner, maintaining close contact only with Eugen, his childhood friend. On Sundays, they would go on walks together from Königsbronn, and he would speak to Eugen about his worries, problems, and plans. “I think I’ll travel,” he told him one February Sunday on the way to Oberkochen, about four miles away. “You know,” he went on, “I don’t really feel content here in Königsbronn.”

In this remark, Eugen thought he heard melancholy and disappointment more than excitement for a journey. Eugen suspected what was making Georg so despondent: his father’s constant outbursts, his alcoholism—and perhaps, he thought, it was also the stark contrast between the peaceful rural idyll and the stressful, hectic life in his parents’ house that aroused Georg’s desire to move away. Was his departure an escape? An attempt to find an orderly life in a new place?

Eugen was uncertain. Should he be happy or sad about his friend’s plans? He would miss Georg—their walks, their conversations, the things they did together, his music, his advice, and his courage.

CHAPTER EIGHT

Departure

On February 26, 1924, an edition of the Völkischer Beobachter appeared again for the first time since the newspaper had been banned after the Hitler putsch, announcing for the following day a meeting of the National Socialists in the Bürgerbräu Beer Hall—the site of the failed coup. “A New Beginning,” read the headline under the newspaper’s logo, in which the words Freiheit und Brot (Freedom and Bread) were now written in small print above the eagle with the swastika, the registered emblem of the Nazi Party. Herausgeber Adolf Hitler (Publisher Adolf Hitler) was written under the title. The Völkischer Beobachter—purchased from the Thule Society, a “Germanic order,” in December 1920 by Hitler and his backers (probably from the Reichswehr) for 120,000 Papiermarks—had been banned immediately after the putsch on November 9, 1923. By then, the National Socialist mouthpiece, appearing in an unusual six-column broadsheet format, had a circulation of 30,000 copies per day.

Until 1922, Hitler had written many leading articles; thereafter, he had his speeches published in the newspaper. His early articles were already hate-filled appeals to his followers’ will to combat. In the March 6, 1922, edition, he wrote:

We will rouse the people. And not only rouse them, we will whip them up. We will preach battle, relentless battle against this whole parliamentary brood, this whole system, which will not cease until Germany is either destroyed or one day some iron skull comes, perhaps with dirty boots, but with a clear conscience and a steel fist, who will end the chatter of these parquet heroes and give the nation a deed.

Now, on February 27, 1925, the Nazi Party, which was itself banned after the November putsch, was to be reestablished under the same name. Hitler had already been released on December 20, 1924, from his prison term, which he later referred to with amusement as a “university at state expense.” The remainder of the sentence from which he had been pardoned was officially noted: 3 years, 333 days, 21 hours, 50 minutes. At the request of the state prosecutor at the Munich Regional Court I, the prison warden had written a report describing Hitler as an exemplary prisoner.

Hitler has shown himself to be a man of order and discipline, not only with respect to himself, but also with respect to his fellow inmates. He is content, humble, and agreeable. Makes no demands, is quiet and reasonable, serious and without any abusive behavior, tries painstakingly to comply with the prison restrictions. He is a man without personal vanity, is satisfied with the institution’s food, does not smoke or drink, and, while comradely, is able to secure a certain authority over his fellow inmates…. Hitler will seek to reignite the national movement according to his principles, however no longer by violent means, if necessary directed against the government, but in contact with the proper government authorities.

On December 20, a telegram arrived from Munich, in which the regional court judge ordered Hitler’s immediate release. Thus his term in the Landsberg Prison had ended. He had been able to spend it in the circle of his followers without any hardship. He ate his daily meals together with them in a large common room in which a swastika flag adorned the wall. Fellow inmates kept his cell in order, handled his correspondence, and reported to the Führer each morning. Life in fortress confinement was reminiscent of the atmosphere in an officers’ club, as the prisoners ordered their favorite meals from the prison guards, smoked, played cards, and could receive visits from the outside as they pleased. There were days when Hitler, who was actually entitled to only six visiting hours per week, received over twenty guests in succession in the “fortress parlor” set up specifically for those meetings.

Hitler also regularly went for walks in the institution’s garden, accompanied by numerous loyalists. And in the evening, when he spoke to his comrades about his ideas and visions, even the prison officials listened, silent and motionless with admiration, to his words.

Hitler used the prison term, which forced him to take a breather from his public political activities, to set down in writing the foundations of his ideological system. Rudolf Hess spent hours hammering Hitler’s worldview into the typewriter. In his writings, he put down on paper what would become a rigorous program after his release: the confessional work Mein Kampf, the first volume of which appeared in 1925 under the title Eine Abrechnung (A Reckoning).

At the event in February 1925 at the Bürgerbräu Beer Hall, the first since his release, Hitler now wanted to gather the countless—occasionally factionalized and competing—nationalist groups and associations in order to present his political goals, visions, and plans. Though the event did not begin until eight o’clock in the evening, audience members were already streaming into the hall in the early afternoon. Two hours before it began, the doors had to be closed. Roughly 4,000 supporters waited expectantly for Hitler. When he finally entered the hall, cheers burst out.

In a two-hour speech, Hitler urged the crowd to forget the past, settle differences, bury hostilities, and under his leadership take German history into their hands. “World Jewry” had to be combated, Marxism toppled. A new beginning was imminent, a new national movement.

Hitler sent his audience into a frenzy of joy. The disgrace of 1923 was forgotten; now there was nowhere to go but “forward.” Was this the breakthrough?

* * *

Less than 200 miles away, in the remote village of Oberkochen, life continued on its leisurely course. It was Sunday. In the Zum Hirsch tavern, Georg and Eugen sat with a quarter-liter bottle of wine and waited for Friedel. Certainly—here in the rural idyll, too—there were nationalist undercurrents, the bogeyman of Marxism could stoke people’s fears, and enemies could be demonized through propaganda. But here there was no trace of a “national movement” as in Munich. Politics was not an issue. That was the case for Georg and Eugen, too. They talked about their plans, their dreams—rarely, if ever, about politics.

In recent months, the two of them had often trekked over from Königsbronn, even when cold and snow made the route arduous. They enjoyed the vastness of the natural landscape, which aroused in them a strange mixture of emotions: the feeling of being at home and the longing to set off on a journey.

They were regulars at the Hirsch. The tavern keeper was a friendly man with a round figure, who brought good inexpensive food to the table and always had time for a chat with his guests. Here Georg had made the acquaintance of Friedel, a robust young fellow from Oberkochen, who was also a carpenter by trade. He had told him about his intention of moving away, and Friedel had given him the address of a master carpenter in Bernried, a small village near Lake Constance, where he himself had once found work during his travels.

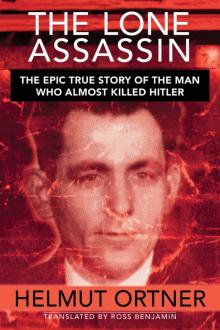

The Lone Assassin

The Lone Assassin